If there is one response as a writer I dread more than a rejection to a pitch, it’s this one: “I’d be happy to talk to you. Why don’t you give me a call?”

When I hear the first few clarinet notes of Rhapsody in Blue, my phone’s ringtone, I’m gripped with anxiety. My first reaction is to hit mute. (Sorry, Gershwin.)

I have always had an aversion to talking on the phone, but I didn’t understand why—until earlier this year. In April, I found out that I am on the autism spectrum. The diagnosis explained why I have to mentally prepare myself before answering the phone and why, most of the time, I swipe “reject” instead.

Most neurotypical people don’t give a second thought about making—or taking—a phone call. But it can be a real problem for those of us on the spectrum. Many of us find social interactions uncomfortable, so we read lips and watch body movements to gather socially relevant cues. But on the phone, all that visual information is gone, and we may fall awkwardly silent or fill gaps with needless talk.

Understanding this has helped me prepare better for phone calls. But I’ve also begun to understand that I owe many of my strengths as a writer to my autism.

A common saying in the autism community goes: “If you’ve met one autistic person, you’ve met one autistic person.” That is, we autistic people all vary in our traits. Some of these are problematic, but others can be beneficial. Because we observe and process the world differently, our writing can present unique perspectives. Autistic writers who learn to capitalize on the favorable traits and manage the more challenging ones can thrive in this profession.

Like most writers, I usually juggle multiple projects. Lately, I’ve been writing a book and freelance articles, and I’ve struggled to retain the details of so many different topics without feeling overwhelmed.

Since my diagnosis, I’ve learned that multitasking can be challenging, if not impossible, for people on the spectrum. We often have a hard time with working memory, the ability to keep ideas and thoughts organized on mental sticky notes long enough to process them. Those of us with poor working memory find our sticky notes quickly scattered, making it difficult to retain specifics and see the big picture.

Sensory issues can also be problematic for writers on the spectrum. Noise, temperature, smells, or visual clutter, among others, can distract us. A leaf blower or loud music can halt my work, and I find myself unable to refocus until the sound ceases. And even then, starting again can be difficult.

People on the spectrum often have trouble with “stop and go.” Once we get going, we can work for hours, and have trouble stopping. But after stopping, we have a difficult time refocusing or changing gears. Samantha Craft, the author of Everyday Aspergers, says autistic inertia can leave her “unable to begin a writing task.” And Laura James, a freelance writer and author of Odd Girl Out: My Extraordinary Autistic Life, says her writing suffers when her routine goes awry. “On a good day I am super-efficient. On bad ones, hours can slip by while I try to get started,” she says.

Perhaps one of the biggest challenges facing autistic writers is “autistic burnout,” a term we use to describe what happens when we become overwhelmed and exhausted. Neurotypicals suffer burnout too, of course, but autistic burnout comes from a different place. It develops from sensory overload, or the stress and anxiety that comes with trying to fit into a neurotypical world.

Those on the spectrum often “mask” when we’re in public to hide or minimize our autistic traits in order to appear “normal.” Seemingly simple tasks, such as phone calls and meetings, can leave us mentally, physically, and emotionally drained, and needing time to recover. This state can last from a few hours to days, or build up slowly and last weeks or even months.

“Even the smallest things can wear me out,” says Eric Garcia, a journalist at Roll Call, which covers the U.S. Congress and politics. “After a lot of taxing interviews, I am not only mentally, but physically exhausted.” Like computers on the edge of collapse, our minds and bodies go into “safe mode.”

But life as an autistic writer is not all bad: It also presents many benefits. We often have better long-term memory than most people. Garcia says this trait is helpful for reporters, who “have to retain a lot information both for the current piece you are writing, as well as for future stories.”

People on the spectrum are also often visual thinkers. In the book Thinking in Pictures, autistic author Temple Grandin, an expert on animal behavior, writes about visualizing “peace” as a dove and “jumping” as Olympic hurdles. Jennifer Malia, a writer and professor of English at Norfolk State University, also uses this form of picture thinking. She recalls key events from her life by replaying “video memories,” a trait that helped her write Too Sticky!: A Story of an Autistic Girl with Sensory Issues, a children’s book based partly on her experience living with autism.

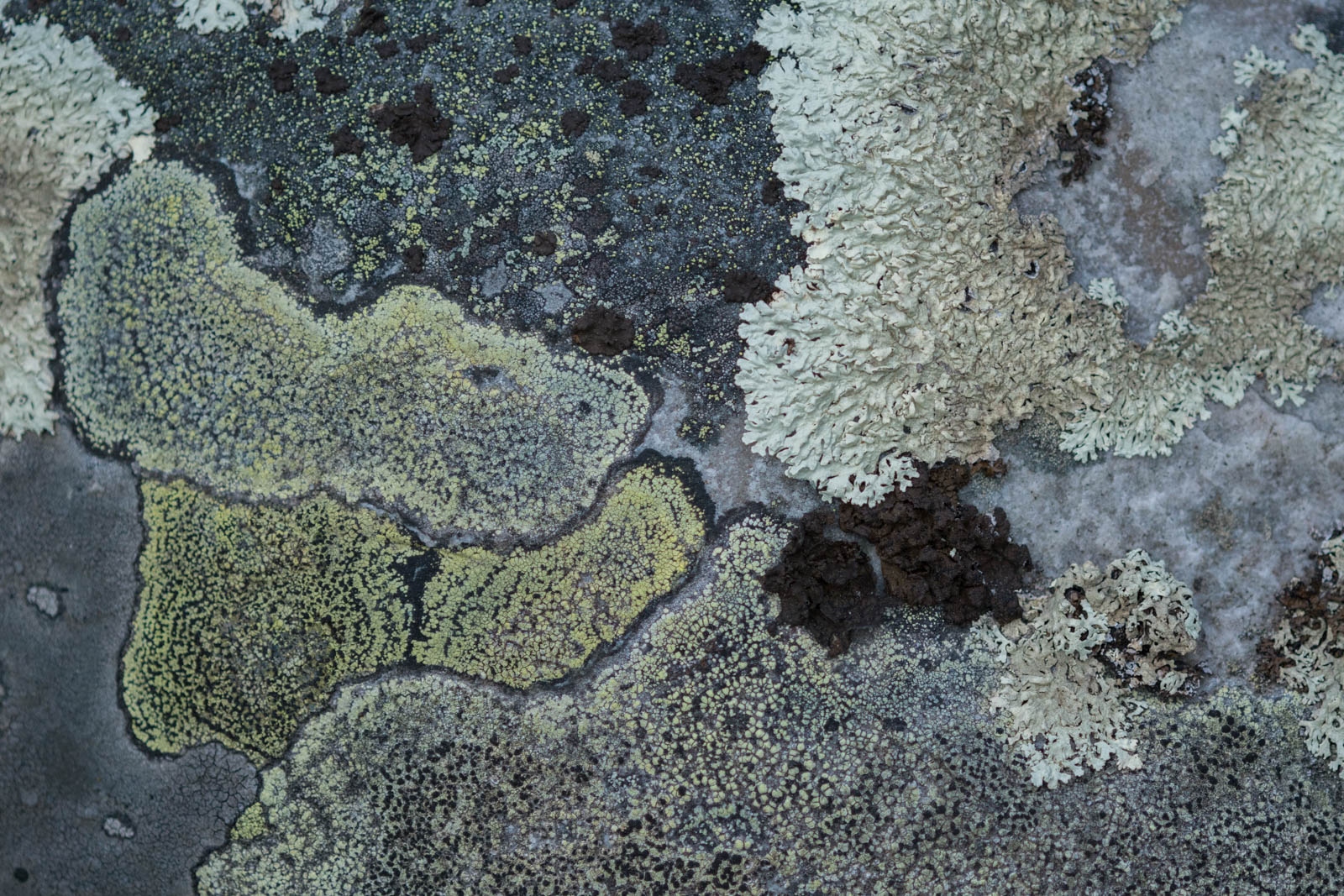

Autistic people also tend to have an ability to zero in on their areas of interest. Many writers have a subject area they stick to or a beat they cover, but this is especially true for writers with autism. We often have the ability to hyper-focus and learn quickly and for long periods of time. Garcia’s niche is politics and disability; mine is natural history, with a specialization in urban nature. I can spend an entire day researching niche topics such as barnacle predators before resurfacing.

This year, I’ve learned that autism defines us, but our traits are part of the whole. “It’s a string of separate paragraphs stuck together,” Leonard Bernstein wrote in 1955 about Gershwin’s masterpiece Rhapsody in Blue. “You can cut parts of it without affecting the whole. You can remove any of these stuck-together sections and the piece still goes on as bravely as before…. And it’s still the Rhapsody in Blue.”

Yes, autistic traits are part of us, but we can learn to manage and even capitalize on them.

I still don’t love phone calls. But now, before making a call, I run through the conversation in my mind, then brace myself and dial.

Kelly Brenner is a naturalist, writer, and photographer based in Seattle. She founded The Metropolitan Field Guide in 2009 and has bylines in Crosscut, ParentMap, and National Wildlife Magazine. She is currently writing a book about urban nature, which will be published by Mountaineers Books in 2019. She’s written about her discovery of being autistic here. Follow her on Twitter @MetroFieldGuide.