One of the most vexing aspects of cancer is that the treatments are so toxic. Chemotherapy aims a full-intensity blast at every errant cell, while pelting normal cells with friendly fire. But cancer cells mutate, and sometimes one of these random changes provides protection from the chemo drugs. When that happens, the cancer cell in question has a tremendous advantage. Its neighbors have all been decimated, so it can multiply unchecked. Essentially, the medicine that was supposed to eradicate a cancer has instead made it deadlier.

In her Wired story “A Clever New Strategy for Treating Cancer, Thanks to Darwin,” published in March 2019, Roxanne Khamsi introduces Robert Gatenby, a radiologist obsessed with a controversial scientific notion—that cancer operates on Darwinian principles. Just as lions and cheetahs vie for gazelles on the African savanna, the genetically distinct cells within a tumor may compete with one another for space and nourishment.

Gatenby, who heads the radiology department at the H. Lee Moffitt Cancer Center in Tampa, Florida, has spent years melding ecology with oncology to develop evolution-based cancer treatments. These therapies aim not to cure cancer but to slow its spread. Doctors deliver small doses of chemo whenever a patient’s cancer shows signs of advancing. The disease won’t ever go away, but patients suffer fewer side effects, and are less susceptible to a calamitous growth of resistant cells. As Khamsi recounts, when a man receiving the new therapy asked, “How do we know this stuff is working?” one of his doctors replied, “Well, you won’t be dead.”

The work is still largely theoretical, but Gatenby encounters less skepticism from other physicians these days, because his technique has recently shown promise for men with treatment-resistant prostate cancer.

Here, Khamsi, who in her day job is chief news editor at Nature Medicine, talks to Jeanne Erdmann, TON co-founder and editor-at-large, about what went into writing this compelling narrative. The task drew on Khamsi’s diverse talents—among them, deciphering technical concepts such as game theory and Lotka-Volterra equations, overcoming an interview subject’s reluctance to talk about himself, and outwitting a determined rooster during a reporting trip to Tampa. (This interview has been edited for length and clarity.)

How did you find this story and Robert Gatenby, the researcher you profiled?

A scientist, Carlo Maley [a biologist at Arizona State University], reached out and told me about a meeting he was organizing on evolution and cancer. Initially I was like, “whatever.” I get a lot of emails about upcoming meetings and conferences, so initially I didn’t think it was something that would spark a story.

But I had a phone conversation with Maley around the fall of 2017. Genetics is my everything, and all of our lives have been touched by cancer, including my own. Those two things intrigued me in combination, and I kept it in the back of my brain. I started PubMedding the topic in January 2018.

Did you just say “PubMedding”?

I guess I crosscheck and poke around in PubMed so much, I started using it as a verb.

Love it. OK, let’s get back to how you found Gatenby.

I stumbled on these papers that were all in a special issue of a journal. I noticed that Bob Gatenby had coordinated the issue and written the preface. He also kept coming up in conversations. Then I found the clinical trial that Gatenby did. He had this theory called “adaptive therapy.”

I’ve noticed that an intriguing term can be a tip-off to a story. Has that happened to you before?

Definitely. As a journalist, when somebody mentions a name for something [that you haven’t heard before], you realize it’s a thing.

Your story came out more than a year after you started reporting it. Why so long?

I got sick. I had a super, super rare thyroid infection, and it was a very slow recovery. Even though I started on this in January of 2018, from February through June or July I was not my normal self. As journalists, I think we don’t talk enough about how life can get in the way, and it takes a while to get stuff done.

Stepping away gave me some added perspective, though. Rather than thinking about the story as a series of experiments, I wanted to follow the human story. I certainly hadn’t envisioned this as a profile when I started out.

What about Gatenby made you realize he’d be strong to profile?

Whenever I spoke with Gatenby on the phone I felt that he was really open and honest with his answers. He really thought about the questions I posed—I could almost hear him thinking on the phone when there was a pause. I knew that he was seen as a key figure—maybe the key figure—in the area of evolutionary oncology, but he was also very accessible and forthright. That gave me confidence to put him at the heart of the story.

Gatenby’s world is not that visual. He’s just a guy in a lab running computer simulations. Was it hard to make his work come alive?

I knew I needed a scene of some sort. When I found out about the Hackathon, a workshop on evolutionary therapy scheduled for late October 2018 in Tampa, I took a week off work to go. The funny thing is, the scene that I spent a week in Tampa for, that I took my vacation for, got cut.

Why was it cut?

It was a tough fit. I knew it while I was there. A lot of the time I was just observing scientists hashing out ideas. I was still glad I went, though, because it did serve the story. I saw a lot of people face to face. I got chased by a rooster, and we can talk about that.

Medical stories usually open with a patient, but in this piece you lead with the story of a DDT-resistant moth with a penchant for brussels sprouts. What made you decide to take this approach?

I don’t think there’s anything wrong with starting an article with a patient’s story. I’ve done it a lot in the past, and I will 100 percent do it again in the future. But sometimes it’s refreshing to read a story that starts a different way. I was really attached to the idea of starting chronologically—with Darwin. But that just didn’t work, no matter how I tried. I have to give 110 percent of the credit to the editors at Wired. It was such a joy to work with them. Very late in the game, like a penultimate round of the draft, they said, “How about we do this?”

When you and I first chatted about this story, you said it was the hardest thing you’ve ever done. How so?

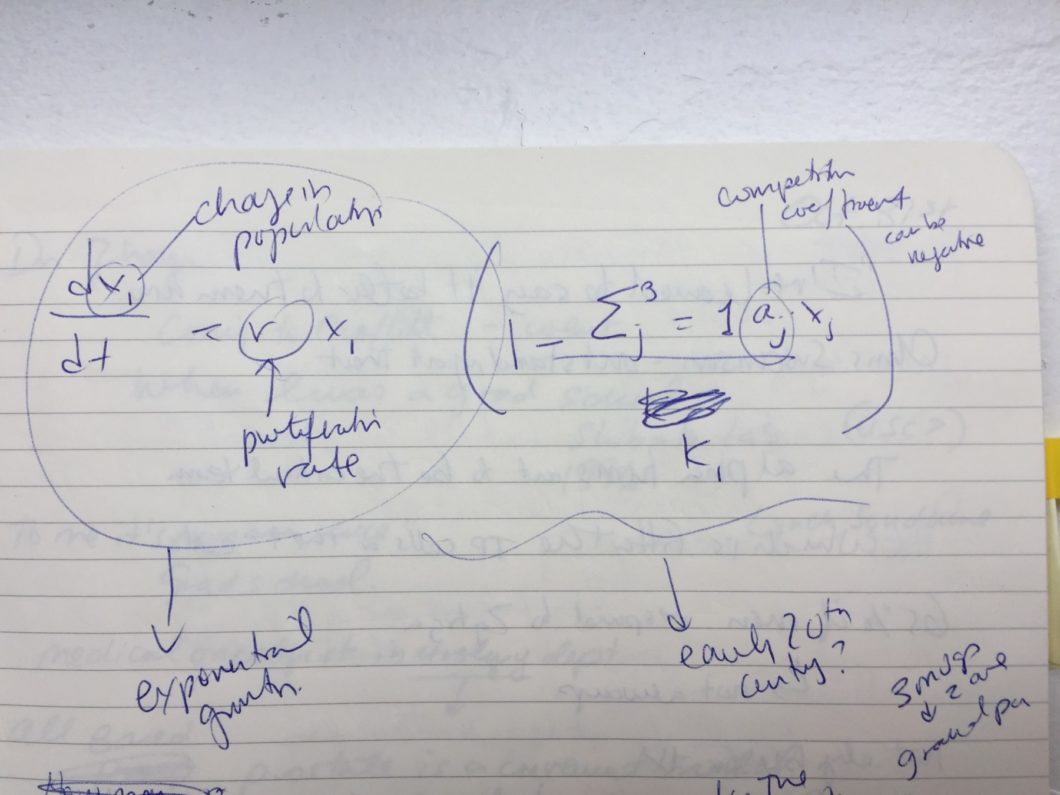

There was so much math I was not ready for. I got an A in calculus, and I had been a cashier. I generally feel fine with numbers, but this was multivariable equations and game theory.

How did you master the mathematics?

I’m not sure I mastered the mathematics per se. I just got to understanding the essential basics, so that I could grasp how their key algorithms worked. At one point there was a researcher, Joel Brown, who answered some lingering questions I had while he was dashing down the jet bridge, being hustled along to board the plane for a conference in Paris. I was so embarrassed to keep going back to the scientists. To be honest, though, I think it really helped.

You present Gatenby’s intellectual development as a rich narrative. Did that information flow out of him, or did you have to work for it?

Sometimes scientists have a prepackaged origin story, but he certainly didn’t. A lot of the stuff didn’t come out immediately. I had to peel away the onion. For example, the breast cancer patients [who were seriously injured or killed by their treatments] whose scans he saw [as a young radiologist]. That wasn’t him just coming to me. That was me trying to delve into what motivated him in the first place to get interested in cancer. He hadn’t thought about this stuff in 30 years. It was lots of walks down memory lane with someone who was, like, “Why are you going down memory lane with me? I am not that interesting.” I had to convince him that it was a worthwhile jaunt.

You included so much history in the piece—how we came to use battlefield language to describe cancer, the breast cancer trials of the 1980s—and made it parallel the evolution of Gatenby’s own thinking about cancer. How did you fit it all into a structure?

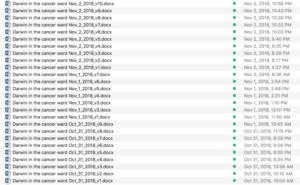

Great question. Can I first say that the structure changed a lot? I have this weird system where every single day, I incorporate the date into the file name, and then I have version 1, 2, 3, 4, and so on. Every time I change something substantially, I make a new version. For this story, I ended up with 198 drafts. I am not saying that it’s 198 different structures, but every time I moved something around, I saved it again. It frees me to be savage with my changes because I know I can always go back to an earlier version if I want to retrace my steps.

For the structure, and how I determined where things go: I did this crazy thing where I made a Word document in landscape style with boxes of text, detailing what each section was going to do: answer this question, and then lead to this scene, and so on. I sent it to my editor and said, “Is this good?” And she thought I was maybe a little bit nuts, but she seemed happy that I was nuts.

And, there was a lot that got cut. So much got cut.

We’ve talked about how your main reporting trip ended up nowhere in the story. What else got cut?

Stuff about Darwin, and on genome sequencing of cancer. I talked to 60-plus sources for this story. There was tons and tons of “What does this mean for industry?” that got cut. I had a whole section on this garden at ASU related to evolution—I was looking at landscape plans and measuring square footage—and that got cut. I just had to, like Marie Kondo, declutter. I don’t actually believe in using her approach for everyone’s house, including my own, but there is something about that thinking—saying, “Thank you, you served a purpose, even though I am cutting you out of my story.”

Before we get to another topic, tell me about the rooster.

When I traveled to the Moffitt Cancer Center in Tampa, I stayed at a hotel that was about a 15-minute walk away. To get to the hospital and research labs, I had to cross through a park with a lake. There were a lot of ducks and a few roosters. As a New Yorker, I got really excited about the roosters. And I wanted to get a good photo with my cellphone. So I crouched down really close to this one huge rooster to get a picture of him pecking at the ground. One moment everything was fine and then the next minute it wasn’t. Something in his bird brain snapped and he cocked his head up and then started going after me. He chased me for about 200 feet—I was trying to swat him with my big black handbag the whole way as I was running, but it wasn’t working. Then, as we got near the parking lot, he lunged closer to me and I threw my entire handbag at him. I also let out an embarrassing yelp. The bag knocked him aside for a moment, so I grabbed it back and scooted away as onlookers in the parking lot looked on, a bit bemused. One person said, “Oh, that guy is a mean one.”

For the next few days, every time I approached the park to try to cross through on the way to and from the labs, the same rooster would spot me and start walking toward me in a threatening way. It was weird because he wouldn’t notice other people. I decided to take the long way around the park instead, to avoid him.

Not many writers can say they had to fight a rooster to get a story! Did you have to fight your editors on anything?

Yes, I coined a term in this piece: endo-evolution. It means natural selection playing out within an organism’s own tissues, and I fought for it to be in the story. It’s my job to capture the words of others, but I think there is a certain amount of joy in trying to add something to the conversation.

You explained so much complicated science, and reconstructed meetings you hadn’t attended. How was the fact-checking?

Fact-checkers are like gods to me, but I never think that they are accountable for the ultimate accuracy of my stories. That person is me, always, so I try to be as fastidious as possible about every word in my stories. I recently started to label papers starting with the publication year in front of the title. Having them organized chronologically is not only handy for fact-checking, it also helps me understand how the scientific knowledge in that field has evolved over time.

On Facebook, you thanked Edwin Dobb, who teaches narrative journalism at the UC Berkeley Graduate School of Journalism, for his writing advice. What was it?

I was at the UC Berkeley 11th Hour Food and Farming Journalism Fellowship with Michael Pollan [in 2015], and Dobb was one of the advisers. He said, “You overwrite. Be simple, be straightforward, be sparing with your words.” He said it in a very kind way and a blunt way. And I was like, “Ok, you are right.” It’s kind of a surgical process where I go back and cut out the fat. Adverbs get trimmed out. Extra clauses get booted. Maybe one day I will write lean sentences on the first try. But until then I have to review each of them and do a bunch of pruning. I try to practice it even in my emails. It’s something I am going to try to work on the rest of my life.

TON cofounder and editor-at-large Jeanne Erdmann is an award-winning freelance health-and-science writer based in Missouri. Her writing has been published in Nature Medicine, Nature, Women’s Health, Discover, The Washington Post, Slate, Aeon, and elsewhere. She is on the board of the Association of Health Care Journalists. Follow her on Twitter @jeanne_erdmann.